Exploring the Ancient Pyramids of Consciousness

by Will Foreman

(Special thanks to Beckett’s Irish Pub in Berkeley where you can drink a draught of Pyramid without waiting for Godot)

Introductory Remarks

Like the Great Pyramids of Giza, the mysteries of consciousness have long been explored with incomplete results. In this essay I hope to offer a useful addition to the literature on consciousness with the assistance of forms from descriptive geometry, especially the pyramid. The pyramidal shape has been used to convey firmness as well as mystery for almost as long as metaphors have subserved consciousness in the human mind. In no way, however, do I wish to imply the stony permanence of the ancient pyramids of the Nile Valley or their mystically inspired, dark, inner, sepulchral chambers.

In a previous work, Foreman, W. (1994) Creating Democracy In Time, I made a brief attempt to explain consciousness. The hard copy edition of that work included a poorly annotated diagram (now improved as diagram 4 below). Appendix 1 added philosophical background to the model. Unfortunately, few examples were offered to clarify how the model might produce a subjective perception of consciousness or awareness. Nor was any explicit attempt made to explain how the brain produces such qualia, i.e., qualitative experiences, as the taste of a pear, feelings of pain and pleasure, or such moods as euphoria and depression. Now I would like to flesh out that previous sketch to make it clearer how I understand consciousness and it’s qualia. [On various attempts to avoid the problems of qualia, see Searle, John R. (1997) The Mystery of Consciousness.]

The holy grail of Western consciousness research appears to be (1) an understanding of individual consciousness, including qualia, (2) an application of that understanding to the building of a machine that would more or less confirm the understanding, and finally, (3) in classical utilitarian style, the machine would–if benignly employed–assist humanity in various ways. The approach taken here will be to emphasize the value of applying our models of consciousness to the further evolution of our own individual and collective minds.

I disagree with Edelman’s contention [Edelman, G. M. (1992) Bright Air, Brilliant Fire] that “intersubjective communication in science must be objective, not projective.” This strikes me as analogous to Descartes’ trying to rescue science from religious politics by conceptually separating the body from the 17th century mind. There is, of course, an inherent difficulty in communicating a model of consciousness so as to produce in the minds of others both a belief and a subjective feeling that the model might actually work. However, in the long run, I don’t think that the task will be made easier by avoiding either the subjective or the sociopolitical implications of the models proposed. The very creation of consciousness in human beings depends, to a fair degree, on the social construction of models of reality. Thus our models, including their unavoidable subjective and projective elements, are based on definitions and values that come partly from culture and will inevitably return to culture, politics and all.

Part of the problem is that models of consciousness are naturally far simpler than the very rich experience of consciousness itself. The brain’s billions and billions of synapses–according to Carl Sagan (1977) The Dragons of Eden–are theoretically capable of more different brain states than there are elementary particles in the Universe. Leaving aside the practical significance of such a comparison, the amount of information present in our environment and the amount of information continuously processed by our brains will always leave a reader conscious of the special vastness of his or her own mind and dissatisfied with any generic simplification of it.

Learning how to think about the human mind implies a simultaneous learning about the flows of information and decision-making in the child as well as through and in other information-processing units of society. Consciousness, as we experience it, is certainly not present in anything other than a biological organism with a central nervous system. Yet without adhering absolutely to either “functionalist” or “structuralist” dogma, I think it’s safe to say that there are similarities between the abstract structures of consciousness and those of, say, a democracy. Thus the search for “secret” processes underlying consciousness is only part of the search for a unified theory of meaning and for ways to understand and improve living systems–in particular, human systems.

Some Disclaimers

So many authors have put forth models of conscious thought–some of them quite sophisticated–that I must apologize if I have inadvertently repeated ideas or concepts which are original to others. The model I create does consciously make extensive use of variations on the cybernetic loops of Wiener, N. (1948) Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and Machine and those of Miller, Galanter, and Pribram (1960) Plans and the Structure of Behavior–as well as other concepts that have worked their way into the subconscious minds of most people immersed in the sciences of complexity.

The model described here assumes different types of memory stores and many possible variations in the type of signal mixing which is done at the “comparing nodes” and at each of the levels of consciousness that are included in the model. Any textbook of neuroscience or on neural network computing can provide a few clues as to the variation and number of types of signal mixing, “comparing,” or “matching” that may occur.

I will try not to assign specific functions to specific brain structures. The reasons for this are twofold: (1) I do not keep up with research in the neurosciences, and (2) I think that there is clear evidence that the brain is, partly, a functionally self-organizing system, i.e., the same tasks are not always performed in the same anatomical locations. Attempts at precise localization of many functions are, therefore, doomed to fail. Rather, we must include a search for processes that retain the same functional relationships as they dance from one anatomical structure to another in accordance with the needs and capacities of the organism.

There is no such thing as a complete explanation of human consciousness. I cannot fully address many of the questions that arise about consciousness–though I still think that the answer to some of those questions may become apparent if one takes the time to mentally follow the possible flows of information over the arrows in the diagrams of the model. I will only try to describe enough of the model to enable the reader to grasp what I consider to be its essentials, and hopefully, to convince the reader that it could actually produce consciousness as we generally experience it.

I should add that I am under the influence of an ideology. The model of consciousness presented below is largely derived from, and illustrates, the structures of the syntropic [syn=together, trop=toward something] systems paradigm, described in Foreman (1994), which I believe will manifest increasingly in products of the human mind–including those of art, science, politico-economic formation, and literature–as we proceed through the 21st century.

On the Order of Presentation

First, the basic, cybernetic I–>R–>O pattern of Input, Referent, and Output is shown with enough added arrows to make it more biologically realistic. This structure represents an elemental unit (a nerve cell, group of neurons, or perhaps a distributed function) of neural processing within the model, and it’s arrows show the flow of signals, patterns, or images. This diagram is explained briefly.

(2) Diagrams 2 and 3 show what I consider to be the prototypical, five distinct “foci” involved in a unit of consciousness and are accompanied by

(3) a verbal sketch outlining the information flows in Diagrams 2 and 3.

(4) Diagram 4, the line drawings and diagram used in the 1994 edition of Creating Democracy In Time, are followed by

(5) another verbal description,

(6) an explanation of qualia, and finally,

(7) comments on the meaning and “teleonomy,” i.e., the appearance of purposive intentionality, in consciousness.

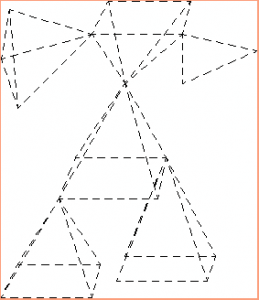

The second drawing presented will be that of the pyramid. Geometric figures representing brain processes are, of course, problematic fictions. They are contrived here only to separate at least five points in three dimensional space from which we can draw arrows and conceptualize flows of information. They risk creating certain misperceptions, but they also help to represent basic units of consciousness. However, redundancy and the need for testing and retesting of input signals in order to achieve such accurate brain models of reality that we can land spaceships on an asteroid are demonstrated, at least partly, by “pyramidal” and “tetrahedral” concepts of the processing of perceptual input.

The penultimate section is reserved for the most difficult task–that of convincing the reader that qualitative experiences such as pain and pleasure can be produced (and altered) by processes described within this model. Finally, we will conclude the discussion with some comments on the relationship of individual consciousness to society and the larger environment.

A Model of Consciousness

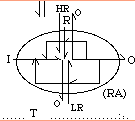

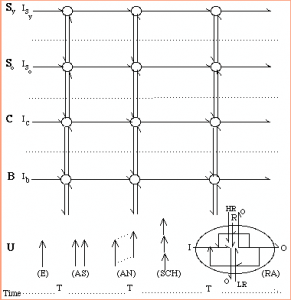

Diagram 1. The Rational-Analytic (RA) Model of an Information Processing Unit

This diagram represents an adaptation of the basic, cybernetic process of decision and control with a feedback loop. One can also see feedforward loops, memory loops, and the site of a mixture or an interleaving, i.e., a rapid alternation of matches, with the different Referent standards against which an Input pattern can be matched or “mismatched.” At least one or several of these units is located at each of the foci or “nodal points” in the pyramid model. The RA Model is, once again, an idealized model that doesn’t describe what actually happens in nerve cells and/or nerve assemblies, but it does appear to simulate some of the simplest functions of “decision-making” in nerve tissue.

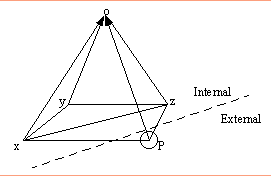

Diagram 2. The Pyramid of Consciousness

Now, with the preceding drawings in mind, let us create a mental picture and a feeling for how it all might work:

Light reflecting off person (P) who, in diagram 2 is standing before you, enters your eyes and stimulates patterns of neural activity at “x,” “z,” and “o” in your brain. Each pattern or “image” may be inclusive of the angles, straight lines, colors, etc. to which some individual neurons respond specifically.

The image at x then fires off at least three output patterns, one of which becomes a Referent pattern at locus z. The second signal becomes an Input pattern at locus y where a “match” or “comparison” is accomplished between a Referent image y, which is a remembered image, and the image from x. The third output from x becomes a Lower Referent input at o, the apex (or “omega” process) of our imagined pyramid. Pattern y, as mentioned, is a Referent memory pattern to which x will be compared. Y could even be a neural competency built by prior experience into the input tracts that then filter pattern x as it comes in. No matter, in this model at least, the match between x and y has to occur somewhere, and the result of the match is an Output signal that becomes an Input signal at z.

At z, the output from the match which occurred at y becomes Input that is now matched with the Referent pattern coming in from x and is interleaved with the pattern coming in as a Lower Referent from P. Notice that the original image from P has been “split” yet arrives simultaneously from two directions at z. This is only somewhat analogous to the process of splitting laser beams and bringing the beams back together to form interference patterns that result in a three dimensional hologram. It can also be likened to the stereophonic effect that results from music coming from separate sources and into two ears instead of one ear. (Interference patterns occur widely in nature and produce an interesting variety of surprising, “special” effects. However, I do not assert here that they produce holograms in the brain.)

Results of the matching process, including interference patterns, are specifically “defined” and given “values” as they flow to become Input patterns or Referent patterns at other stations in the brain where other pyramid structures are applied to test and retest other aspects of the model of reality that is being formed, piece by piece, in many pyramidal testing units. The output from z, for example, is sent on separate paths to become motor action and/or unconscious process at B and U levels (see diagram 4 below) in the model, and simultaneously, toward matching processes at the C, So, and Sy levels of the model.

C-level, or primary, consciousness occurs when patterns at z are interleaved, matches are tested and retested to ensure accuracy, specific features of the perceived external and/or internal reality are represented as signal “patterns,” some of which are then “defined” by attaching “marker” patterns, and given various “values,” i.e., additional “marker” patterns. Ultimately, “values” are brain patterns that are attached to autonomic patterns and physiological parameters necessary for survival of the organism and/or the values attached to other organisms or objects related to needs and preferences. Thus a relatively complete or functionally adequate “model” is created of real-time objects in space and relations among them. Each such “model of reality,” having been well-tested against previously well-tested models of reality, becomes virtually indistinguishable–to the host of other functional patterns in the brain–from the parallel process of reality itself. The closest we come to a direct contact with external physical reality, however, comes to us through the long evolutionary experimentation with the survival value of various sensory input patterns and “reflex circuits.”

When the Output from the matching process at z begins to flow into o as Input, it is matched again to patterns arriving more directly from P as Referent, it’s matches are interleaved with matches occurring against Lower Referents which came from x and y, and a Higher Referent which comes from symbolic stores or memories of prior thoughts, intentions, time-and-sequence codes, and/or other consciousness-level patterns. From the matches which occur at this level we obtain further “definition,” attach further “value,” and our internal model takes on yet greater meaning. The process of achieving a subjective experience of a consciousness of both Self and Other–with all the attendant, qualitative features–is also under way. It is the result of a growing “accuracy” of representation, definition, and valuing. Insofar as our internalized model of the “Self” is then able to act competently in relation to our now internalized model of the real-world non-Self, the internal models are now being confirmed as “real,” i.e., our brains are creating models that we interpret as real-world stuff because they work when tested.

When our brain models of “Self” and our models of “Other,” each interacting with the other in a process that is “parallel” to the world outside our brains, achieve desired results–sometimes even predictive validity–and our internal models are thoroughly tested against real-world realities, then the “illusion” of our “direct” perception of reality begins. Even as our internal models coincide accurately with external reality, the reality of models that are built up “beneath” waves of neural excitation remains hidden “behind the scenes.” Or to put it another way, our “illusions” disappear as our models become the “reality” to which we respond successfully.

It’s important to note that a single pass through each of the loci in a pyramidal system would not likely produce even a flash of conscious awareness–though it may register in the unconscious mind. An ongoing stream of time-sequenced, rapid-fire matches at each loci may be essential for consciousness. Similarly, a vast amount of parallel processing of related information (for example, ambient light, sound, and temperature patterns; proprioceptive information about body position; autonomic signals generated by internal organs, hormones, and chemical ratios; “limbic reports” on emotional reactions to perceived internal and external information, and attentional process) participates on the production of consciousness. Matching patterns from the different sensory modalities of sight, hearing, odor detection, taste, and tactile sensation all combine to produce that vivid experience of “brilliant fire” that can’t be fully reproduced by “virtual reality” machines but is reproduced expertly in the brain as memory, imagination, or dreams.

In a few hundred milliseconds the brain proliferates thousands of “pyramids of consciousness” at several, dynamically changing locations and scales of size. These units are rapidly sequenced and elaborated to build the complex models of external and internal realities which are continually tested, adjusted, and further developed throughout life. Our models of the external world and its general laws of nature evolve to become so accurate that it is little wonder that we feel we are directly perceiving reality itself.

Each of the dashed lines represent a path of information forming much as described in the explanations of diagrams 1 and 2. Inputs and outputs could be located at numerous points.

Diagram 3. Building a Model of Reality: Proliferating Units of Consciousness

Diagram 3 shows the interactions among pyramidal processes forming the larger structure of a “model.” We see at the bottom left a pyramidal process forming on the basis of sensory inputs of one modality, such as vision, and another to the right forming on the basis of, say, tactile input. Output patterns are then brought into correspondence when a representative pattern from each modality is put through the pyramidal matching, testing and retesting process against those patterns coming from the other modality. Each confirms or disconfirms the accuracy of the other. As these flows and comparisons go on inside each pyramidal structure, other structures of matching Inputs to Referents with resulting Outputs are taking place as a proliferating build-up of the neural model proceeds.

This diagram could represent a person putting on a pair of pants. Seeing the pants, holding them with the hands, feeling the sensations of the pants around each leg, perhaps beginning to form a mental image of how the Self will look after the pants are on, all become parts of the model building that could be going on in diagram 3. When our neural models are doubly or triply confirmed by matching defined neural patterns from two or three different sensory inputs, especially from different sensory modalities, our subjective feeling of an accurate and vivid perception of external reality is heightened. Try covering one eye and one ear as you perceive a person coming toward you. Do you not feel a vague sense of unreality, perhaps even a slight apprehension?

And still the foregoing can only be a small part of the story. Neither consciousness nor complex models of external reality were programmed by our genes. Consciousness has to be developed over long minutes and years of internal model building experience with millions of sensory inputs, trial matchings and errors, and further evolved with associative and analogical processes built up in the brain from the simple perceptions of objects moving in space. Models of Self and Other(s) are crucial. No small contribution is made, for example, by mothers or fathers who speak in dulcet tones, reaffirming each of us as a “Self” of value.

Learned epigenetically in individuals, consciousness has to evolve through feedback loops of motor action, testing, and of communications that pass through cultures and back into the individual brain to help us achieve “definitions” and “values.” Since “defining” and “valuing” are so necessary to guide our behaviors toward individual and species survival, as well as to various other levels of purposeful action, and to the subjective experiences of qualia, we will address them in more detail below. First, however, let’s look at the “deep evolution” of the structures and types of consciousness.

(E)=extropic form of conscious/unconscious information processing. (The single arrow here represents the simple appearance of an information pattern that flows until it is interrupted or stopped.) (AS)=associative form of conscious/unconscious information processing with the double arrow representing two or more patterns of information flow that tend to be associated with one another, (AN)=analogical form of conscious/unconscious information processing with one arrow (patterned flow of information) causing the appearance of a like pattern, (SCH)=schematic form of conscious/unconscious information processing in which the arrows represent automatic sequences in the flow of information patterns, (RA)=rational-analytic form of conscious/unconscious information processing in which patterns flow in, are compared or mixed, then flow out to meet other inputs or out to effect an action, T….=time sequences in the above network or lattice of information flows

Diagram 4. The Syntropic Model of Consciousness

The above diagram and following explanatory comments are designed to provide some understanding of attentional, intentional, and stream of consciousness phenomena. This two-dimensional drawing is intended to be used as a starting point for imagining a large, three-dimensional lattice connected to a human body with its sources of energy and all of its internal and musculoskeletal organs. It can be imagined to contain even a human personality with its playfulness, urgencies, emergencies, and its sacredly-held values. Information flowing over such a lattice could form a huge variety of informational patterns and shapes that change with time.

The arrows in the diagram represent flows of information patterns. Five paradigmatic structures of information flow, labeled E, AS, SCH, AN and RA, are shown at the U level of (un)consciousness. These symbolically represent Extropic, ASsociative, SCHematic, ANalogical and Rational-Analytic processes respectively and are described more fully in Appendix 1 along with two more complex paradigms of information structure, the dialectical-systemic and the syntropic patterns–and “chaos,” which is the name given to that set of unorganized, spontaneously occurring “random events” that are present in every system.

Each of these paradigmatic patterns are to be imagined as superimposed on the network of information flows (including flows through pyramid patterns and “models”) shown above the U level. As we go through stages of cognitive development, each of these paradigms of information processing takes a turn at being the predominant, identifying structure or mode of functioning. The small circles where the heads of arrows come together for a “comparison” or “mixing” of inputs are “RA nodes.” Each of the RA nodes has the functional structure of the I–>R–>O pattern of Inputs, Referents, Outputs, and the feedforward, feedback, and adjustment loops shown in the bottom right corner of the diagram.

The RA unit, together with its feedback loops, is the smallest unit of a consciousness pattern. A “conscious” system cannot be constructed using only the simpler units of information processing which are shown to the left of the I–>R–>O pattern (the RA structure). Diagram 4 shows again the possibilities of comparing or mixing at each node with at least two or three inputs, with split signal processing, interference patterns, and with interleaved matching of patterns (each of which could be simply a summation of inputs). Further, information flow from each node can be modulated or filtered, and the results can be compared with further input patterns which may be Higher Referents (HR) and Lower Referents (LR).

However, at least one of the Input patterns coming into each unit of consciousness must be split so that a remixing or interference occurs together with two or more interleaved comparisons or mixes among several inputs at each node. The Inputs at each node are put to a matching or mismatching and the result is an output from the node. A number of arrows in the diagram bifurcate, showing split signals that then feed back or feed forward to modify one of the other Inputs to a node. The reader can undoubtedly appreciate the almost infinite variety of patterns of information that can develop in a four-dimensional network like the brain. Only a miniscule number of the possible connections and variations of flow among the RA nodes of a complex network can be described–but enough, perhaps, to achieve a fundamental feeling for the complexity that underlies both consciousness and any other advanced, information-processing system such as an authentic democracy with its plethora of feedback loops designed to improve the fidelity of signals, “honesty,” efficient decision-making, and progress toward goals.

The intensity or strength of any signal can influence or be influenced by any information flowing to the arrow that represents it. The strength of a signal could be signified by altering the thickness of the arrows or assigning (+) or (-) numbers to each arrow. We can assume that signals related to basic survival or to sexual desire, or any intensely felt emotion, are often “strong” enough or repeated frequently enough to modify, or predominate over, other inputs and outputs.

The single stream of consciousness with sustained attention occurs at the C and So (self-observing) levels when inputs and outputs are held to a sequence of closely related images or patterns. The C level stream is achieved by matching, feedback, and feedforward to the next time frame–all of which occurs at subliminal sequencing speeds. Sampling and feedback control frequencies of the higher level processes can occur at different rates than lower level consciousness streams as they hold the attention to specific tasks. This may be one of the reasons for the specific EEG frequencies associated with focused attention. Intentional consciousness and behavior imply a larger purposive action that binds microsequenced processes into macrosequenced frameworks.

The Perception of Awareness

The “fullness” and the partial unpredictability of conscious experience are, once again, facilitated by: (1) the vast storehouse of memories and reference values, (2) the huge variety of inputs that may occur from the outside and from internal state reports, (3) the enormous number of information flow paths that occur simultaneously in the massive, parallel processing that is constantly occurring, especially at lower levels in this lattice, (4) from the multimedia (multiple sensory modalities) experience of the world around us, (5) from the fact that, depending on the strength of signals, an “intrusion” of inputs to or from C or the Sy (syntropic) levels may result in a new focus or a redirection of the flow of consciousness at any time, and (6) the more or less constant testing and verifying of reality via sensory input patterns and reflex circuits.

With regard to the richness of conscious awareness, it may be interesting to add that there is experimental evidence supporting the view that the “unconscious mind” can continue a search through memory stores at a rate of about thirty items per second even after the conscious mind has moved on to other subjects. And as a further aside, according to the above model of consciousness, every thought or verbalization at one level of consciousness is also a “suggestion” to other levels of consciousness; hence, the common experience of trying to remember something momentarily forgotten then finding that the unconscious searching process may be improved by consciously saying to a friend or to oneself, “Perhaps you’ll remember that in a few moments.”

Consciousness must be thought of as occurring in various degrees and at several levels. We can define “C level consciousness,” most simply as the sequenced process of one after another “mappings or matchings” of a C level neural reference pattern with split inputs that result from the outputs of B (perceptual) level matching processes. The ability to concentrate, or to maintain a “train of thought,” depends on the ability to repeat or feedforward the matching process with the remembered same, or a similar, Referent while the Input to the next timeframe varies with “real time” changes in the environment or imagination. Sudden shifts in the “train of thought” without an awareness of the shift may occur at the C level if movement occurs that invokes neural pathways related to survival needs, if spontaneous events occur at subneuronal (perhaps even at subquantum) levels, or if the shift is initiated purposively at the Sy level.

C level consciousness, which we share to some degree with other mammals, enables one to be aware of both the outer environment and the inner environment including autonomic information, to model that mixture of perceptions, and to choose among possible actions. The B level input patterns may come from outside the brain or from other parts of the brain. The B input and reference patterns may come from different primary or secondary sensory processing areas or from memory stores. Again, confirmation and filling out of the “3-D, stereophonic, or multimedia experience” of the world and of one’s conscious self occurs when patterns from different sensory modalities are “compared,” and associatively reconstructed as space-time models.

The C level “pattern matching” is of essentially the same structure as the other matching patterns except that it’s C level input patterns come from the results of B input-reference matching processes which are then output to a matching process with C level reference patterns that are more specific to C level processing. The C level process also has the capacity to send signals which may influence B level matching processes and, to a lesser degree, can influence the U level mental processes.

“Observation” or monitoring (sampling) of C level conscious process is “self-consciousness.” “Self-consciousness” or self-observation, with a limited ability to direct conscious flow, is the So level “pattern matching.” The subjective phenomena of “self-consciousness,” that may occur along with shyness for example, results from an So level observation of a C level modeling of the way other people may be thinking about one’s self. The Sy level pattern, i.e., the syntropic level, has the capacity to create, control, or influence the flow of So, C, many B, and many U level processes in a purposeful direction. Depending on the strength or number of signals, of course, processing outputs from any level may modify the information flow at all the other levels. This is how special strategies can make self-conscious modification of autonomic processes possible.

The So level process is what we commonly call the “self-observing ego.” This processing is “passive observation,” that is, it doesn’t actively direct the processes that it monitors, though the act of observation may interrupt them. Vipassana meditation, said to be the method practiced by Siddartha Guatama, is–at least in its elementary form–the practice of So processing, and it is indirectly self-therapeutic to the extent that formerly automatic associations among somatic, sentic, and cognitive processes can be interrupted, allowing them to be replaced by healthier associations.

Sy information processing is a different, more active, creative, and purposeful level of “self-consciousness.” It adds the capacity for active modification of the self or for telic influence over the processes under observation, and it is the level of consciousness that we seek to acquire, maintain, or strengthen in certain other meditative practices, such as autogenics, self-hypnosis, and focused attention on performance goals.

Levels and Forms of Consciousness

In Diagram 4, B-level consciousness is the base level of perceptual input. Signals from the external world then go up to and through C-level matching processes and simultaneously down to U-level processes where incomplete pyramid patterns more frequently occur, and therefore, patterns less frequently rise to consciousness. The vast storehouse of information in the unconscious mind sends signals up into consciousness patterns, thereby influencing conscious information processing. Sometimes whole patterns from the unconscious are unearthed and brought to the pyramidal patterns of consciousness.

“Unconscious,” or U-level, information processing includes all the U level forms included in diagram 4. At the U levels, information processing tends to be dominated by the associative and analogical paradigms. Unconscious processes, which by definition cannot be easily observed from the C or So levels, are nonetheless amenable to Sy modulation, as previously mentioned, via special cognitive strategies that utilize memories and imagination.

In unconscious information processing several paradigmatic form-types of information flow occur independently and simultaneously–many of them without time markers added–in many parts of the brain. For that reason unconscious processes often appear timeless and sometimes remarkably efficient by comparison with conscious processes which are more complex, and more “single-channeled,” in nature. The downside of this timelessness is that sometimes learned patterns of thought and behavior which serve a person well at one time are expressed maladaptively, i.e., neurotically, at a later time. Those information patterns and images which at higher levels are “sequence marked” to time, language, or both linear and circular cause-effect patterns are naturally those which can more easily become knowable “in time.”

Now, let’s look briefly at the paradigmatic types of consciousness, each a distinct pattern in the organization of signal processing. At the bottom of Diagram 4, a series of patterns of interaction is depicted as the “extropy,” “association,” “analogy,” “schematic,” and “rational-analytic” paradigmatic forms. “Chaos,” dialectical-systemic, and “syntropic” are not given graphic representation in the diagram but are described in Appendix 1 of Foreman (1994) and in chapter 4 of the online edition of that book. The reader interested in a more complete version of the syntropic model of consciousness is referred there. The pyramids of consciousness described above fall into the Rational-Analytic type of structure, but as we build elaborate models in our brains, these pyramidal processes can also be strung together in larger patterns that fall into any one of the other paradigms.

Even such neuronal substructures as microtubules and the elementary particles of atoms can spontaneously, i.e., “chaotically,” undergo a change that leads to a cascade of changes in neuronal firing patterns as well as changes in relationships among neurons, neuronal groups, and pyramidal patterns until ultimately the whole organism’s behavior and relationships begin to fall into a pattern that was triggered by a random event. Nature in general tends to evolve through the paradigmatic types of organization that culminate in more complex, qualitatively different degrees of organization. Each new level in the model combines with and adds significance to those forms incorporated from simpler levels of organization. Further “chunking,” or abstracting, of “whole system” information achieves more universal “truths,” i.e., higher level generalizations about subsumed “chunks of information,” or patterns of information.

Definition, Value, and Qualia

As previously mentioned, through the evolutionary process we have arrived at a brain that creates a very complicated system of definitions and values, primarily in relation to pain and pleasure. It uses these to promote the survival of the organism, related organisms, and of consciousness itself. If our species and our selves are to survive and prosper, we must, for example, learn that it would feel painful to jump off a cliff or pleasurable to make love. Thus we create “definitions,” which are neural patterns of linguistic and other symbols or markers attached through learning to perceptual and other neural patterns. “Values” are also neural patterns that attach positive or negative significance to perceptual patterns, symbolic patterns, and concept patterns that relate, ultimately, to the physiological and behavior patterns involved in survival. Degrees of strength or intensity are attached to each value pattern.

Signals from x, y, z, and o, shown in Diagram 2, are sent to portions of the brain that subserve emotions and moods as well as to those lower regions that contain autonomic (physiologic and homeostatic) centers where the signals are matched, and signal patterns from these matching foci are sent back into pyramidal patterns where they can be matched with patterns representing linguistic symbols, “definitions,” and “values” at C, So, and Sy levels of consciousness.

The qualitative aspects of sensation and experience arise from the (1) multidimensional sense of the “reality” of qualia achieved by pyramidal processes that generate accurate models of reality and then attach their “truth value” to associated definitions and values, (2) the “definitions” that we learn to give to neural patterns of sensation and experience, and (3) the type and strength of value that the brain attaches to various perceptual patterns. If the person (P) who is standing before you happens to be someone you love (value strongly) and haven’t seen for a long time (value even more strongly), then his or her presence is defined as a “happy” occasion and the strong values attached send signals that move the body toward the loved one while also sending signals into limbic or emotional areas of the brain and into the autonomic system to produce a pattern of changes in heart rate, blood pressure, adrenalin levels, skin, and so on–all of which are perceived in feedback loops that lead to further confirmation of definition and value at both conscious and unconscious levels–thus producing the qualia of subjective experience.

If, on the other hand, the organism at P is biting your leg and foaming at the mouth, then the qualia of pain and fear exacerbated by catastrophic thoughts of dying or of a horrible death later by rabies will naturally be defined as highly threatening to the survival of your body and to the immediate survival of your consciousness. The subjective quality of the pain is determined first by defining the sensation as “pain.” When coupled with extreme danger to survival, however, your mind may exclude the definition of pain while you focus attention on necessary action. At some point, though, a defined sense pattern is immediately given an extremely intense, negative value, while cognitive processes add to a framework of impending catastrophe, emotional and autonomic patterns specific to pain and danger are evoked, feedback perception of these changes are confirming, and the whole experience of the pain and extreme danger is made worse by the pyramidal process of bringing you the pain in its “3-D or IMAX” version complete with ambient sights and surround sound–including, perhaps, the sound of your own screams.

Now, in the actual safety of our surroundings, let us reflect a little more calmly on what “just happened.” There were no teeth crushing your brain tissues, no dying body falling from your prefrontal cortex onto your limbic organs. The “pain” and the “danger” was perceived as real enough alright, but at the moment of the happening, they were actually just neural patterns in the brain that modeled the animal, its bad behavior, and sensations in your leg. And those neural patterns or models could only have been constructed from a mixture of anatomy, definition, and valuation. Too often, philosophers of the mind either deny the subjective experience of a qualitative feeling or they reify it, asserting that the feeling is real and unexplained as though it were a new species of structure, something other than a pattern of neural and physiological activity. The “pain” was there only because a neural pattern was there that was defined as “pain,” and that definition with all its meanings and the strongly negative values attached to it were further “confirmed” by all the thoughts, emotions, and physiological changes in the body that accompanied them–and soon would have been further confirmed or modified by social and cultural processes.

In truth, either by focus on necessary action or by previous training, you may have been able to quickly achieve an altered state of consciousness within which you could have reduced or eliminated the experience of pain by redefining the sensation and/or focusing your attention on other aspects of the whole experience.

Naturally, with regard to this latter possibility, it would not have been wise to simply eliminate the pain. Taking quick action to save yourself was necessary, though, and that is just the point. “Pain” is as essential to human survival as is reproductive desire. That’s why efficient pain fibers, tracts, and “pain centers” evolved, and that’s why natural selection chose a brain that learns to define certain neural patterns as pain while attaching such strong negative values, i.e., “qualities,” to them. It is worth noting, however, that in certain cases most of the anatomical structures known to subserve either pain or pleasure can and have been destroyed, leaving only elusively moving neural patterns that continue to sustain the qualitative experience of those sensations.

On the Meaning and Purposes of Consciousness

Of what real value is consciousness? Does consciousness contribute to survival, or is it likely to lead to species self-destruction? How does consciousness relate to society and vice versa?

Much of modern thinking and research on consciousness focuses on the individual brain. The scientific, reductionist approach if strictly applied would have us isolating the brain completely for a more objective analysis of its parts. And indeed, more than one animal brain has died while laboratory scientists were too busy to remember the needs of the whole animal. Further, when we isolate the whole human being for relatively short periods of time, as in sensory deprivation experiments, the object of our study, consciousness, begins to fragment and disappear.

It seems clear to me that consciousness evolved because it was naturally selected, possibly as a part of group selection, and that it is not merely a byproduct of evolution. The advantages obtained by binding time to the will of the mind, by enabling symbolic communication to organize large numbers of our species, carrying out projects that span generations and continents, to foretell the death of our planet, and to transcend the boundaries of the earthly environment ought to be obvious. Along with every great leap forward in human powers, new dangers are encountered. However, not all forms of consciousness evolved during our earlier period of life in the original environment of evolutionary adaptiveness, and whether those early forms will be sufficient for solving the problems of the 21st century is at question.

Recalling Einstein’s statement that nuclear weapons have “changed everything save our ways of thinking,” I am inclined to believe that this is a still growing truth that today encompasses several newer and more pervasive threats to human survival. For example, just as governments, our presently defective organs of species consciousness, were slow to discover the idea of “nuclear winter,” so too we are late in arriving at an understanding of global warming. Concomitant with our narrow-minded technological progress, each hour brings us closer to probable, or at least possible, catastrophes of our own making. Only a vastly improved, collective consciousness of an order not yet manifest in our global systems can assist us.

Literature on the processes of individual consciousness can reinforce the self-indulgent individualism of certain, short-sighted cultures, or it can lead to healthier ideas about the relationship of individuals to the whole human community and to the ecosystems that support us. Actually, societies that promote excessive individualism tend to be dominated by forces of material wealth and their mass media, which too often leave the individual’s model of Self weak and poorly defined. Information flowing into the person outweighs self-differentiating speech and action output, and the Self feels ever more powerless and insignificant.

Most of us are capable of self-observing levels of consciousness as, for example, when we observe or recall the particular thoughts we have (or had) about events that occur at particular times. Likewise, we can learn to observe and categorize the repetitive patterns of thought and behavior into which we and our societies sometimes fall–patterns that may be destructive to ourselves and/or to our environments. However, the antidote, personal development of So and Sy level cognitive abilities, usually requires conscious effort or training. At a societal level, public awareness of the need for economic and political reform are essential. We cannot persist forever in practices that destroy the bases of our own survival.

Constructive thought and action patterns could be taught to most everyone, beginning at birth. They can be formally rationalized around the age of 11 or 12, and periodic refresher courses can be encouraged throughout life. The differentiation of the S levels of consciousness is best learned in association with others of like purpose. As with any skill, most persons can improve their abilities at either So or the more difficult Sy levels and forms of consciousness. These are psychophysiological skills that anyone can develop. Contrary to the belief of some, they do not require the mystical or supernatural trappings that are sometimes attached to the higher structures of consciousness. Societies of the future [see Foreman, W. (1994) Creating Democracy In Time] likely will have a higher percentage of citizens with So (system-self-observing) and Sy (system-purposive) levels of consciousness, and along with those skills, fewer health problems, much less violence, more peace of mind, and much greater wisdom. [See Foreman (1994) Creating Democracy In Time for examples.]

The relevance of this model to social forms comes, firstly, from the cross-level hypothesis that consciousness and democratic process have structural similarities. If true, it could be useful to observe the patterns of information processing within ourselves and compare them to the models of the democratic process that are available. Democracy, then, could come to be seen as conscious intelligence expanded to a higher level of organization–the conscious mind externalized and made observable as a social process–not as the mind of a giant organism but as intelligent action at a different level of humanity. The benefits could flow in both directions–to and fro between our understandings of individual consciousness and of the democratic process.

To continue the evolution and improvement of our democracies, we ought to be able to recognize, at each level of individual consciousness, the differences among democratic, authoritarian (abusive), and disorganized or anarchic processes–especially as they occur in families, schools, and corporations. It would be unrealistically ideal to hope that all the individual citizens of a democracy would ever have an equal ability to participate in improving the democratic processes instead of practicing outmoded authoritarian skills. Nevertheless, each “democracy” would be wise to begin working toward that ideal before the stresses of global environmental crises begin to tear at the fabric of civilized value systems.

Incorporating models of democratic process into several levels of consciousness could easily be accomplished. By starting with children of an early age and placing more mass media bandwidth under public control, for example, we could achieve a citizenry that more quickly identifies the elements at fault in a complex democracy when it is not producing good results. A more comprehensive education in the consciousness of authentic democracy may be necessary to distinguish between an elected representative who is truly working for the common good and one who is not, or a mass medium that presents a biased view of political events–and one that does not.

The value of the So level self-observing ego, and of methods of developing or strengthening Sy level consciousness ought to be more apparent after a glance at this model. A well-developed Self-and-Other consciousness, so essential to the principle of isonomia, (equality of access and participation) in democratic politics, becomes mutually respectful and empathic interaction among citizens.

Finally, a democratic social-change organization, in order to function more effectively, could use all of the paradigmatic patterns and feedback loops hypothesized as necessary at higher levels of consciousness in the brain to produce the “conscious” and “self-conscious” foundations of purposeful social action.

Thus are consciousness studies first and foremost a subset of the search for optimal change at several levels of human organization.